How do I find my purpose in life?

With help from utopian literary theory (and from Deborah Levy)

Dear Emma,

Please can you suggest some fictional therapy for people who are still or again figuring out their purpose in life. It does change, all you 20 or 30 somethings. So be prepared (or excited?) to grapple with what it all means again, only this time it's more likely to be while waiting alone for the foot doctor than in a bustling cafe.

Thank you for your wisdom and suggestions.

The word I found most interesting in your letter was that bracketed, interrogative, flirty little verb, ‘(excited?)’. There it sits, coyly in parentheses, as if you are toying with the idea that the next stage of your life could be thrilling. Do not toy any longer. Exclamation mark excited! I think it sounds not just ok but inspiring to still be figuring out your purpose later in life. In fact, in the eternally spine-tingling words of Sheenagh Pugh - who I previously quoted to a correspondent who felt stuck at work - ‘Who wants to know / a story’s end, or where a road will go?’

Perhaps you think I am approaching your problem with the starry eyed naiveté of one of those 30 somethings you mentioned. To that I will say, you follow my column and therefore know my age, so you got yourself in for this. I do understand that seeking purpose at a time in life where you have more responsibility, shakier health and possible dependents comes with unique and vexing challenges. But I also think that being older might mean you have greater reserves to draw on, less fucks to give, and a well of experience that can make finding meaning easier. I will return to this.

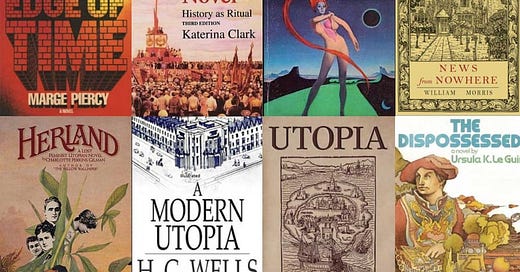

Firstly, however, I want to talk about literary utopianism; something I’ve been studying lately because I’m writing a play that’s set in the future (this is going to circle back to you, I promise). As part of my research, I asked a couple of academics who study literary utopias if they’d ever read about one they’d like to live in. They both said no, which I thought was curious. If a utopia is supposed to be the depiction of a perfect world, why does it almost always seem so unappealing?

One answer to this paradox is that dreaming of things which do not yet exist is an essential part of what makes us human. In his book Utopian Horizons, Cziganyik argues that ‘the capability of human language to express non-existent states of affairs - for instance, wishes and conditional or future sentences - is a unique ability that makes human culture exceptional’. Perhaps we fear a flawless world because in it we would have nothing left to wish for. Cziganyik quotes George Steiner:

We endure, we endure creatively due to our imperative ability to say ‘No’ to reality, to build fictions of alterity, of dreamt or willed or awaited ‘otherness’ for our consciousness to inhabit.

Do you see where I’m going? A perfect world, in which you have it all figured out and in which every one of your dreams has been accomplished, might not be a world you’d want to live in anyway. Actually, it’s this place you currently inhabit - in which you have to, in your own words, ‘grapple with what it all means again’ - which has the capacity to be so life-affirming. You will probably find what I’m about to say unbearably naive and also laughably grandiose, but the thing that used to scare me about being 50 wasn’t that I’d still be looking for purpose - it was that I’d be so successful and sorted that I’d have nothing left to strive for. (Now I’m no longer 19, I realise this is unlikely to be the case, haha.) I probably ended up with this strange belief because we so rarely see the hopes and dreams of older people (ok, older women) depicted in films and books in the first place, which tend to focus either on youthful aspiration or on aged, epic male ambition (auteur, imperialist conqueror etc). So I loved reading this passage many years ago in Deborah Levy’s memoir The Cost of Living, in which she reminds us that it is possible at any age to build intoxicating fantasies about the future:

I flash-forwarded to my seventies, and saw myself typing at the edge of my swimming pool in California. I would be a legendary sun-damaged genius of cinema, known for typing in my swimming costume, surrounded by verdant tropical plants which always open the mind and make something happen. At lunchtime my staff would shake up my cocktail and toss fresh squid on the barbecue… Yes, my sunlit garden in California would be full of chirping colourful birds. The bird clock in my London apartment was just a rehearsal for the real thing.

The Cost of Living is, by the way, a witty, astute and empowering book about defining yourself in middle age, which I highly recommend if you haven’t already read it.

What I am trying to do is dispel any feelings you might have that it is embarrassing to still be ‘incomplete’ at your age; still living in conditionals and ‘imagined alterities’. Far from it - this is exactly the quality that makes you uniquely and essentially human.

This is all well and good, you might reply, for someone who has a future fantasy. But your problem is more existential - you still need to build this dream; to construct this sense of purpose. Here I think utopian theory can offer guidance again. Another argument Cziganyik pursues in his critical study is that literary utopias should not be understood as blueprints for real societies, but as imaginative exercises whose inherent fictionality enables us to ‘break the rules of monolithic and static ideologies’. In fact, utopian thinking is ‘less concerned with achieving ends than with visualising possibilities’, and should therefore be ‘considered as process or method, rather than finite destination’.

I like this argument, and I think you could engage in a kind of utopian thinking in order to get closer to discovering your purpose. This is different to goal-setting or reflecting on your values, mind you. When I think about my goals I might write down, say, getting my play on next year. There’s nothing wrong with this, but you could argue that setting my sights solely on the next step of my career leaves me trapped in a limited or ‘static’ capitalist ideology such as Cziganyik described. When I think about my values, on the other hand, I might write down ‘kindness’ or ‘curiosity’ - again, nice, but how do you actualise something so vague? However, when I try to imagine what my utopian world would look like, my answer is different. For example, I think of a society which values and enables close connection with friends, rather than centring around romance and the nuclear family. This feels like a vision that could actually guide and inspire me: I’m not going to go and live on a commune, but I could make small changes to my life that prioritise friendship. And perhaps this realisation will influence what I write about next, too - even though I say I value friendship, all of my plays so far have had romantic love at the heart of them. Maybe my next writing project should explore the intimacy and complexity of friendship.

So, here’s the exercise: write down three things which are integral to your vision of a perfect world. One could be more personal, one could be on a local community level, and one could be nationally or even globally. Try not to get depressed about the fact that your perfect world isn’t achievable in its entirety - none of us can end war overnight. Remember that utopian thinking is about visualising possibilities rather than achieving ends. Instead, let your vision steer you toward small points of action that hopefully feel more steeped in meaning than whatever it is you’re currently doing.

That’s one idea. But honestly I think you should try lots of things. If you were helping a child figure out what they liked, you wouldn’t just do this through conversation and reflection; you’d put a paintbrush in their hand and see if they enjoyed putting colourful splodges on paper. I think you should throw stuff at the wall: do some pottery, join a football team like

, or volunteer for a cause you care about - even if you hate it, you’ll get valuable intel on what horrifies you. When I’m writing, I adopt a similar strategy: I often find out what will work by starting with what doesn’t. So, I write some crappy dialogue for a character, and then as soon as it’s on the page, I can see what’s wrong with it much more clearly than when it was only crappy in my head: this person would never speak so directly. They would be more sarcastic. They would try to joke their way out of the situation. And then I can delete it and do it better. In writing as in life, we learn by doing.One other thing I’ll say is that in a few succinct lines, your letter made me laugh, so you’re obviously a good writer. And an advantage you have as a person with a few decades under your belt is that - whether it’s been bad or good - you’ve experienced a lot. Could you find purpose in sharing what you’ve learnt with others? I’d certainly love you to advise me: in fact, many of my favourite Substacks are written by women slightly older than myself who are bravely redefining their lives, such as

and The Shift with . I was just hanging out in the comments section on ’s Substack yesterday - a good place to go if you want to connect with other women seeking authenticity and purpose - and read this great line by : ‘I almost feel like it’s my calling as a woman in midlife to tell young women the truth about the origins of marriage and its affect on women in the present’. This truth, I must know about, so I’ve already signed up to read Amy’s work. And the best thing about finding purpose through passing on knowledge is that it’s better if your own life hasn’t gone entirely to plan - you’ll have far more to wisdom to share. Even if you don’t want to write about your experiences, I think you could find meaning in other forms of mentorship, whether that’s bonding with a niece or looking into brilliant mentoring programs like this one I used to work for.But if you do decide to start your own Substack or write a novel, and you don’t mind losing your anonymity, then please let me know. I for one am dying to hear it all: what you thought your purpose was in your 20s, when you decided you were wrong, how much you despised the pretentious pottery class I suggested etc etc. I also want to know how it went with the foot doctor. I’m proud of you for striding once more unto the breach, and grappling again with the baffling, exhilarating meaning of it all. Some people don’t bother. Your life is richer for the seeking.

P.S. I mentioned

above but if you are looking for inspiration and ideas about navigating life’s big changes then you should definitely read her Substack Changes with Annie Macmanus. And, the very articulate has written a book about reinventing yourself as a no-longer-20-or-30-something-year-old which might inspire you - You can read more about it and purchase here.P.P.S. I realise I didn’t write directly about the getting old part of your problem, but I did tackle aging in a previous post, if you’d like to read it:

If you enjoyed this post, I’d love you to restack it, share it with a friend, or recommend my Substack to anyone you think might enjoy a regular dose of books + facing the void. Thank you!

Excellent response!

Thank you so much for the shout out! I really appreciate it 🥰