In the first chapter of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, each of the March sisters makes a resolution for the coming year. Even if you only know the Greta Gerwig version of the story (no shame, it’s great), you’ll probably be able to guess what the girls pledge: Jo resolves to keep her temper; Meg to be less vain; Amy to be less selfish; and Beth resolves simply ‘to be all that Father hoped to find her when the year brought round the happy coming home.’

It’s a great way to start a novel, if a little on the nose: we’re immediately aware of each girl’s fatal flaw, and wonder if, or how, the story’s trials and tribulations will help them to surmount it. (Beth is flawless, so doesn’t have a journey to make - instead, she’s the martyr whose tragedy serves as catalyst for her sisters’ growth.) As New Year’s resolutions go, however, I think we can all agree they’re pretty bad. They’re vague. They’re overly ambitious. Beth’s is, frankly, impossible.

Most of us have made a resolution like this at some time or another. A few nights before the big NYE I was at a dinner party sitting next to a lovely man who told me his New Year’s resolution was ‘to be less shit’. Upon further enquiry I found out that what he meant by that was going to the gym more, eating healthily, working harder, quitting smoking, drinking much less, not procrastinating and all the rest of it. Maybe because I’d had a few glasses of Prosecco I was frank with him about the fact that it was his resolution that was shit, rather than him, and managed to wrestle him down to the more specific and attainable goal of going to the physio to get his bad knee seen to. Seems quite urgent, I hope he gets around to it.

I don’t like New Year’s resolutions much. So often they seem to revolve around a desire to cling to an older version of ourselves - someone thinner, more sociable, less cynical - instead of actually embracing the new or the present. In other words, setting wildly optimistic resolutions can be a way of avoiding the much harder work of becoming comfortable with the person you actually are. Then there is the other thing, the way that failed resolutions make us feel like failures ourselves; weak willed slobs who can’t go a single month without eating sweets or drinking (I only lasted three weeks without booze. Ok, fine, 18 days - I broke on the third weekend).

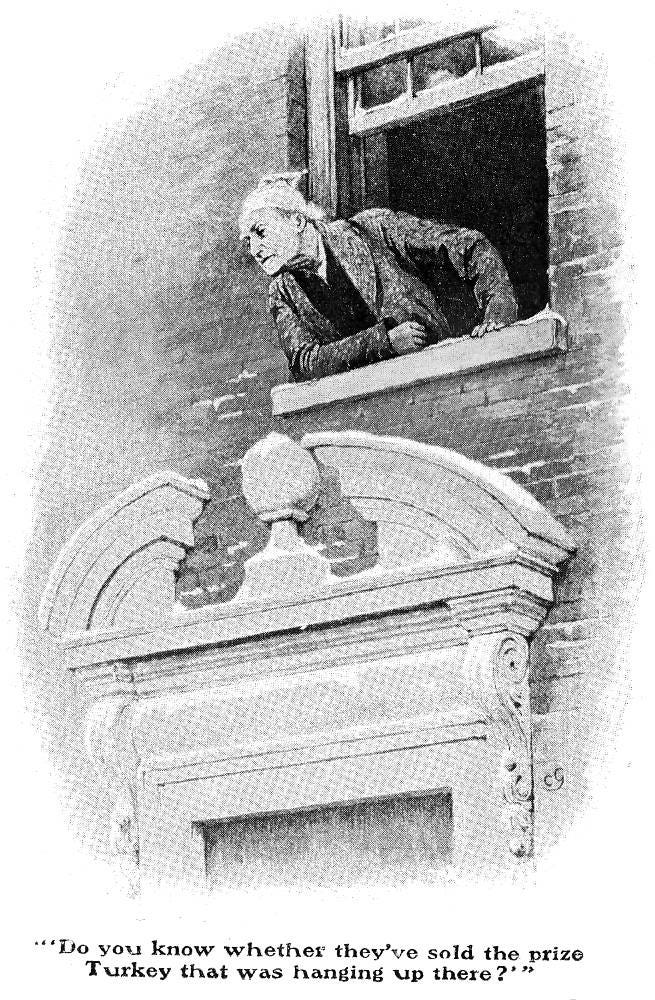

But to say that the desire for self-improvement is a bad thing would not be right either. In fact, it’s quite the opposite: to identify something in yourself that needs to shift, and then actually shifting it, is a hero’s journey so momentous that it is at the heart of all good literature. It’s Scrooge on Christmas day. It’s Darcy, humbled and apologetic at the end of Pride and Prejudice. It’s King Lear, similarly humbled, similarly sorry. It’s all those March sisters we talked about. There’s no denying that oftentimes change is valuable and important. So why are we all so consistently bad at achieving it? Are we really more stubborn, deficient and lacking in self-awareness than even Scrooge, Darcy and King Lear?

Plenty of self-help books will give you answers to this paradox that revolve around setting achievable goals and building habits over time. Your willpower is like a muscle, these books seem to argue - weak right now but with the capacity to become strong through small changes repeated over time. There’s something in this. But the most helpful framing of the problem I’ve ever come across is in Will Storr’s The Science of Storytelling, a kind of hybrid book that uses insights from neuroscience to think about how humans work and explain why some stories are so endlessly compelling to us. In a chapter on creating three-dimensional characters, Storr discourages us from thinking about our identities as cohesive and singular. Instead, he suggests the inside of our heads contain ‘different models of selfhood, constantly fighting for control of who we are’. Storr references Eagleman’s The Secret Lives of the Brain to make a case for the brain as a battle ground for multiple ‘neural narrators’, each at times arguing their case ‘passionately and convincingly, and usually winning.’ Of course we do have a core personality, mediated by culture and life experience. But this core is more like a ‘pole, around which we are constantly, elastically moving’. Reconceptualising the brain in this way leads Storr to think that:

The problem of self-control isn’t really one of willpower. It’s about being inhabited by many different people who have different goals and values, including one who’s determined to be healthy, and one who’s determined to be happy.

I like this way of thinking about self-control. It is not as if you are letting yourself down by having four cocktails on a Tuesday night when you run into an old friend. It’s just that the version of you who thinks it is important to honour serendipity and pursue pleasure won out that day. And when you don’t go out to work drinks and you’re berating yourself with labels of lazy and misanthropic, perhaps it’s more that you were being guided by a neural narrator who felt that rest, comfort and solitude was the right objective to pursue in that moment.

How does this help me keep my New Year’s resolutions? Well, it doesn’t exactly, but it sort of does. Nowadays when I am about to do something like binge three episodes of Traitors (if there’d been more, I’d have binged them too) or accept a large tequila shot I ask myself: is this the version of myself I want to be tonight? Do I want my fun-loving neural narrator to win the battle? And if I do, then I try to accept the consequences (aka: the hangover), because sometimes it’s important to have fun. And if I don’t want them to win, then that little moment’s pause is sometimes enough time to hand the reins back over to my more diligent self. Then I can wake up early to steaming coffee and a clear head without FOMO, because I know I made a conscious decision to let my abstemious neural narrator win. It’s kind of like Inside Out, actually. Wait, am I just describing the plot of Inside Out?

So this year, make big resolutions like the March sisters, or make small, careful, thoughtful ones, because change is at the heart of every good story. But when you fail to transform from ugly duckling to sumptuous swan overnight, remember that we are all part-swan and part-duckling already. And there’s nothing wrong with being a duckling every once in a while.

We are all part-swan and part-duckling already. I like that 👍🏼