Dear Emma,

A feeling of guilt seems to be a permanent fixture in my life. I used to think I would grow out of feeling this way, but as I age it’s only getting worse. Times that I feel guilty include: when I eat unhealthy food (like a big bowl of pasta/ cake / sweet things/ anything that leaves me feeling full), when I say no to friends because I have other plans or need to work etc, and whenever I am not working. I don’t really know how to relax. I even feel guilty about writing this message - because you have more important things to do? Because at this age I should be able to sort this out by myself?

I don’t really understand why I spend so much time feeling like I’ve done something wrong. I had a happy childhood and am currently in a good relationship with someone who never makes me feel this way, or certainly never means to. So why do I feel guilty all the time, and what can I do about it?

Let me start by reassuring you that you do not have to feel guilty about writing to me. I run an advice column, so I literally do not have more important things to do. And if you were able to sort your problems out by yourself, I’d be out of a job, so really you’re doing me a favour.

But I have plenty of friends who struggle with feelings like yours, and I know that offering reassurance is like putting a bandaid on a broken arm, or bailing out a sinking ship with a thimble. It might provide a moment’s relief, but the next day (if not the next hour) will bring something new to feel bad about. Guilt, for you, has become a way of moving through the world, and no amount of external reassurance can fix that. Change will have to come from within.

I think it’s interesting you use the word ‘guilt’ to describe the sensation you live with. Guilt, after all, can refer to two things: the bad feeling you get after a moral transgression, or the fact of having committed a crime in the eyes of the law. But it is not illegal to eat cake, nor is it morally wrong. It’s certainly not morally wrong to be bound by the laws of physics, and therefore unable to be in two places at once. And unless you are seeking the counsel of Elon Musk/ a team of investment bankers (in which case, we have a new problem) you must know it is necessary for bodily functioning to balance work with relaxation. So how is it that you have come to ascribe an ethical value to your core biological needs of sustenance and rest? Who or what has tricked you into feeling this way?

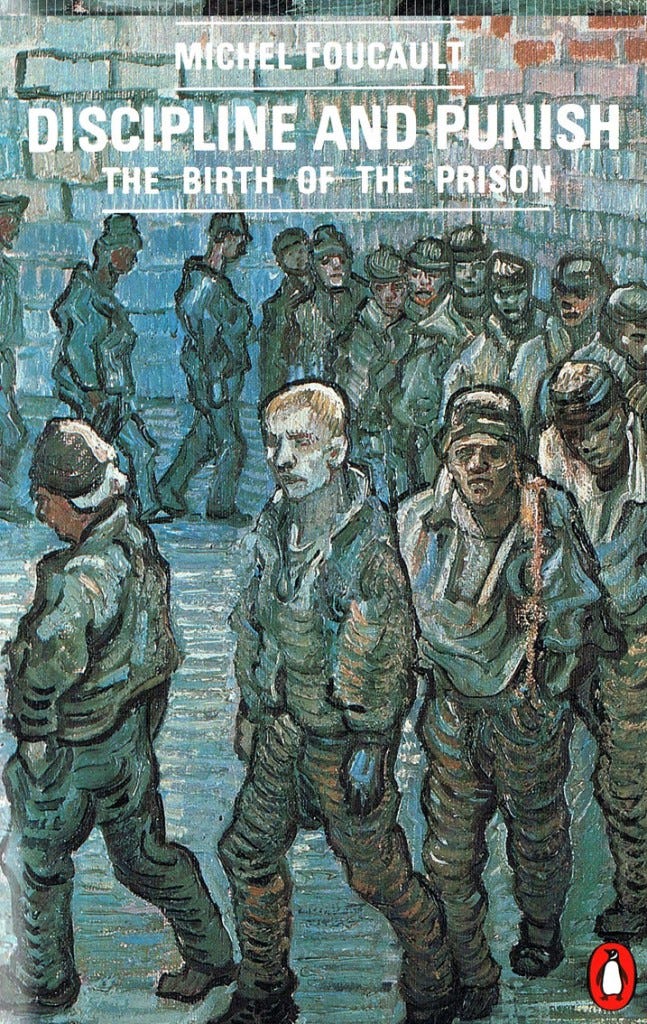

Your problem - particularly the ravaging effect it is having on your body - reminded me of the seminal work by French philosopher and historian of ideas Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish. The book is many things, but primarily it’s a history of the penal system. In it, Foucault argues that in the 18th century we saw a shift away from public, theatrical spectacles of torture toward more private systems of punishment designed to ‘act in depth on the heart, the thoughts, the will’. Modern disciplinary institutions (most obviously, prisons) use regulation of the body - for example, strict scheduling, uniforms and exercise drills - with a view to creating conforming, ‘docile bodies’, suitable for labour in factories (linking this form of discipline directly with the needs of capitalism). Schools, barracks and hospitals employed similar character reforming techniques: Foucault cites the École Militaire, whose ‘shameful class’ was forced to wear sackcloth, conditioning a connection between shame and non-conformity. For Foucault, these new systems of discipline are epitomised by the Panopticon, a prison designed in the 18th century (but never actually built). The building is imagined so that a single guard could, in principle, be watching any prisoner at any moment from a central guard-tower. The fact that inmates cannot know whether or not they are being watched compels them to self-regulation, even when unobserved. Why discipline people, when you can condition them to discipline themselves? Foucault thought the principles of panoptic surveillance were destined to ‘spread throughout the social body’, influencing all ‘instruments and modes’ of power, becoming a tool by which hierarchical organisation was maintained.

As with all sweeping claims about history, there are about a thousand ways you can challenge Foucault’s argument. But it’s a compelling thesis, and it’s certainly an interesting way to think about your own problem. You tell me your feelings of guilt are not created by your personal relationships, so I’ll take you at your word. Instead I think a number of coercive forces are acting on your body - the tools of capitalism and patriarchy - meaning you have become, like Foucault’s prisoner, ‘the principle of [your] own subjection’. Think about all the ways powerful corporations want to make you feel hyper-observed: those rings circling women’s cellulite in the newspapers of the 2000s; and more recently and insidiously, the praise levelled at women for ‘bravely’ showing their grey hairs (can you even see Jessica Biel’s greys in those pictures?!) If you feel guilty about your body, you are weak and distracted; easier to control and exploit. Then there are the highly schematic work routines propagated by entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley, which diffuse their way down into ‘hustle culture’ (but ultimately benefit those same tech corporations in the end, when we all use their apps more and stay longer at the office). And then of course there’s social media - I wonder what Foucault would have made of that. Instagram et al. feels like the final stage of the Panopticon: we are not being observed against our will, but choosing to offer up our lives for constant observation by the prison guard; choosing to let our bodies and behaviours undergo constant judgement and dissection. And it doesn’t seem at all surprising that the most popular Tiktok videos are so often those which glamorise impossibly aspirational daily routines.

It’s strange, isn’t it, that you are working all the time not because you fear being punished but because you have internalised a belief that relaxation is ethically wrong. But you’re certainly not alone. Last night I was walking around my apartment doing laundry, thinking about the issue you are facing, when I realised I was holding in my stomach. I am living by myself at the moment. I mean, what? Talk about Panopticon. The scariest thing is I don’t think I would have even realised I was doing it, if I hadn’t been thinking about your problem at the same time. So thanks for writing in. You are helping me too.

Foucault’s book seeks to challenge the idea that prison reform was driven by humanitarian concerns. Instead he suggests that reformists realised sporadic, individuated torture spectacles were a less systematic way of keeping bodies in check, and existing power relations operating. The thing is: maybe I’ve just drunk the post-18th-century-cool-aid, but - I do think it’s more humane to encourage people to be governed by their conscience, rather than by a fear of being drawn and quartered. The question is, whose conscience are you being governed by? I’m not sure it’s yours. I don’t know why you are more susceptible than others to messaging that harms you, but speaking as someone who’s clearly swallowed a lot of the same stuff: I’d guess you’re a people pleaser. You want to fit in. You’re generally receptive to other people’s ideas and pride yourself on that. But all these nice qualities mean you have internalised an ideology designed to discipline and punish you. So, one thing I thought you could do to counter this is have an active think about the values which govern your own conscience. What might they be - kindness? (Or at least, no intentional cruelty?) Strength? Honesty? The pursuit of pleasure? (Can the pursuit of pleasure be a moral value? Hey, why not?)

Once you have drawn this up, stop using the word ‘guilt’ to refer to the feeling you get when you break a moral code invented by someone you don’t respect. Maybe you could use the word shame, instead - I am being shamed by capitalism. Elon Musk is attempting to shame me. (I am feeling very hostile toward Elon Musk at the moment, can you tell?) Then try to turn that feeling of shame outward into anger, rather than inward, into guilt. Anger is a force you can harness into rebellion, into a middle finger attitude the next time you eat pasta. The forces you are wrestling with are really strong, but they are not indomitable. I truly believe, with practise, with determination, you can slip through the prison bars and out into the glorious world that is waiting for you. Fight the good fight. Enjoy your food.

XX

Thanks for reading Fictional Therapy! I’m happy you’re here. If you’d like to support my work you can consider becoming a free or paid subscriber :-)

Or, you can submit a problem for me to answer here. My inbox is always open.

This was wonderful.

Another who wrote about the way the powers-that-be instil guilt and fear was Gilles Deleuze. In a lecture on Spinoza he observes that 'inspiring sad passions is necessary for the exercise of power' and in the Dialogues he spells it out: 'We live in a world in which the established powers have a stake in transmitting sad affects to us...They need our sadness to make us slaves. The tyrant, the priest, the captors of souls need to persuade us that life is hard and a burden, to repress us, to make us anxious, to administer and organize our intimate little fears'. Thanks for calling this out... Although there may be plenty of occasions that genuinely evoke the 'sad affects', as you say some of the time we're being angled into these feelings by vested interests.